We filed our taxes last month for the LLC we created for About a Donkey, which means we had to get all our bookkeeping perfectly in order. This inspired me to share some numbers with our peers. I believe in transparency as much as possible, and offering other filmmakers context to know what is possible - and where the sacrifices lie for such possibility. So, here's how things shook out. After all fees were taken out, we received $17,671.02 from our Seed&Spark campaign. The film in its entirety, production through post-production, cost $22,485.96 to make. Kelsey Rauber and I made up the difference out of our personal funds. We'll have to do the same for festival submission costs (which I'm determined to keep under $500 via super selective submitting and having access to waivers through the Seed&Spark Filmmaker Rewards), and for deliverables to whichever fests we get into. I'm hoping we'll be able to recoup those funds when the film is eventually streaming on platforms. Regardless though, we made an entire feature for under $23,000, and didn’t break our own banks doing it. I made a film in this range before, with my first feature, Summit. That was made on $21,000 when all was said and done with it. I advanced in many key ways this time around, though.

For one, with Summit, I raised just under $12,000 (after fees) via a crowdfunding campaign. The film was supposed to cost $15,000. I set a goal I felt I could achieve and would make production possible, knowing I’d have to self-fund $3,000 on a credit card. I did not know I would take out 2 additional cards to cover the amount we went over the $15,000 budget, though. I was in debt for a few years because of it (which I’ve only recently recouped via streaming revenue). With About a Donkey, the projected production budget was $20,000. We anticipated self-funding post-production for around another $2,500. We didn’t have confidence in the timing of our campaign to incorporate platform fees, potential declined charges, and contingency funds into our goal, so we decided to just shoot for our $20,000 production budget with the possibility of stretch goals while knowing we had enough personal funds set aside to make up the difference out of pocket, if needed. All of that considered, we actually came in $14.04 under our projected costs for completing the entire film! And while no one was paid for Summit (aside from Sound, who mainly worked for the cost of renting his equipment, and later our DP, deferred), everyone was paid for About a Donkey. (Not much, but something - I'll come back to this.) I learned a lot making Summit and was able to stretch a dollar further while increasing the production value and standards for About a Donkey. And lastly, I finished the film in half the time! Summit was shot over 11 production days during 16 consecutive days on location. We knocked out the intense principal photography quickly, but the film was in post for two years. About a Donkey was shot over 12 days for 4 consecutive weekends (Friday through Sunday), and was in post for nearly 9 months. Both times around, our sound mix took the longest - largely due to our lack of budget. But at the end of the day, About a Donkey is a more polished film, and that (among other things) makes me proud.

A lot of people ask how I do it — make the films I make on the budgets I work with. I explored that a bit with my #ShootingSummit blog series years ago, which you could read. I can sum it up, though, in saying that that time it was a sort of naive experiment that had no business working out but somehow (luckily) did. This time, I actually kind of knew what I was doing. We had what I would call a successful shoot that resulted in a solid film. We made our days, often early. We spent the amount of money we intended to. There were no major setbacks, like getting a DIY process trailer stuck between two ditches on an icy road in the middle of the woods in the dead of night (seriously, #ShootingSummit). Shooting About a Donkey was a lot of work; but I imagine it looked easy from the outside. (Not hashtag worthy.) And that's largely due to the experience gained from the first time around and the preparation taken in pre-production to accommodate the constraints of little money and little time but a lot to do. So below is a breakdown of how we did that.

Before I get there, I should say that this script was written (by Kelsey) in 2012, and we’ve been talking about making it since then. We initially imagined a $250k budget where we could pay everyone well and collaborate with a robust producing team. However, when it became clear that we don’t (yet) have access to acquiring that kind of money but no longer wanted to just wait for some opportunity to come knocking because the story felt timely and necessary and worth making NOW, we set out to figure out how we could just do it, and do it well, and all on a budget we could raise via crowdfunding. What we figured out is what I call Community-Driven Filmmaking.

Wearing All the Hats.

I directed About a Donkey, but I was never just the director on set or off it. I was also the lead producer and handled most of the prep before each shoot (budgeting, scheduling, contracting, communication, shopping for wardrobe, securing locations) that would normally be executed by other paid producers or crew. And on set, I was responsible for making a lot of decisions not just related to the creative direction of the film. It required a lot of forethought on how I would handle certain situations, like should director-me want more time or to experiment creatively but producer-me needed to keep moving or solve a logistical problem. (And then throw in needing to simultaneously direct scenes with a donkey in them while safely managing a set with donkeys on it, and you get some interesting hat-balancing tricks.) It was not easy, but necessary in order to get this film made -- and also how I think I function best. I'm a creative person, but I can't shut off the operational and hyper-organized part of my brain -- it wants (needs) to be in the know, even if it's focusing on or prioritizing the artistry in any given moment. Doing this and being able to do this is key to working in this (no)budget range.

Not Wearing All the Hats.

But I wasn't doing all of the above alone -- not this time. For my first feature, I was the sole producer, as well as the writer & director. I spent much of the shoot anxious and overwhelmed, and constantly playing catch-up with a poorly planned shooting schedule (I had never made a feature before and didn't employ anyone who had). The conditions were more grueling than anticipated, which slowed us down and added obstacles only experience could've prepared us for. With About a Donkey, I had not only Matt Gershowitz, again as my AD but this time not a novice, having taken on more responsibility as an associate producer in pre-production, but also Kelsey as the writer and my co-producer for the film. Kelsey doesn't fully have the production experience (yet) to always be able to answer the questions or solve the problems on set, but she's an excellent project manager and communicator, and was there by my side to be point of contact where possible. And as the writer, having her on set created the opportunity to go to her and say “this isn't working,” when needed. With Summit, I’d have a feeling in my gut that a line wasn’t sitting right or a story element wasn’t adding up because of changes that needed to happen in the moment. I’d need to make quick fixes to the script, but my brain was so weighed down from the stress of the shoot and finding the right words and ways to work with the actors under the circumstances. It was nearly impossible to go into writer-mode and come out with anything but something lazy. With About a Donkey, while I participated in the revising of the screenplay with Kelsey before production, I never had to try to turn into a writer on set. I could instead leave her to do what she's best at, while I worked with the actors or the camera a bit, and then come back to brilliant options to choose from. Ultimately, film is all about collaboration. Just because you can do all the things, doesn’t mean you should - and often you’ll end up with a stronger film if you don’t. That’s something I’ve had to learn over time.

Film-Family, Literally.

I like to think of my collaborators as family. We’re all in this together, every single person is a piece of a puzzle that wouldn’t be complete without every single piece. Being professional and getting the job done is important, but I like my sets to also be fun and supportive. I tend to bring on the same crew members again and again, not just because knowing how each of your team members operates and handles situations leads to efficiency, but also because I like them, as people! We enjoy each other’s company. We respect each other’s skills. We love making cool stuff together. I always aim to create an environment where every person has a voice, feels appreciated, and knows they matter no more or less than anyone else. Yes, there is above and below the line in roles. But there is no above and below the line in treatment. I once had an actor on set who felt they were above speaking to or eating meals next to the below the line crew. That actor never ended up in any of my future work. That crew that the actor refused to acknowledge as equal human beings has been part of all my latest projects. When I say #filmfamily (see instagram), I mean it and want my team to feel it.

My family showing up to be extras.

All that said, I did write “literally” in my header. Aside from the budget being raised through our audience via crowdfunding, we also received an abundance of in-kind support from family and friends. All our locations were loaned, from using my extended family members’ houses to turning the front of my apartment building into the front of a news station to getting my cousin's firefighter friend to allow us access to his firehouse's event space for a prom set. The crew and much of the cast bunked together in our locations (and watched movies each night!) to save on commute costs and get the most out of our turnaround time. Food was made by my mom & cousin for free (we covered the ingredient cost but they volunteered their service). I borrowed cars from family to transport people, never having to rent a vehicle. Props were largely derived from scavenger hunting through relatives' homes and through the creative eye and interesting knick knack collection of our Art Director Nicole Solomon and Post-Production Associate Producer Sean Mannion. And even the donkeys were free! We covered costs to house and feed them for the weekend they were on set (in my mom’s backyard), but the owners of the Donkey Park Sanctuary, Steve Stiert and Larry Futrell, allowed their appearance in the film for free; and Steve & Larry themselves volunteered their services as caregivers/trainers on set. Our story about a donkey creating positive change resonated with them. Our mission aligned with theirs. We made it clear that we cared about taking care of the animals on set, and we included them in the storytelling process. I think that passion and inclusion attracted good people who wanted to help us out and be part of this special thing we could make together. (Truly, check out the good people behind Donkey Park Inc.)

The lovely people and donkeys at Donkey Park Inc.

I’m privileged to have the supportive family I have; but my point is that this kind of “family” support can come from anyone in your community. People don’t have to be filmmakers to be part of making a film. Allowing people to participate in the creation of a project, and making them feel recognized and appreciated, and giving them a sense of ownership in the role they played is how we got this film made (and how I think all films should be made, regardless of budget).

Alternative Compensation.

As I said earlier, everyone was paid, but no one was paid what I would call well. ( Kelsey and I weren't paid, of course; but everyone else was — even down to our one PA.) This is ultimately where most of our money went - to paying the nearly 30 people who worked on the film (followed closely by the cost of production insurance). But even so, in order to do that, everyone worked for below standard day rates. To make this work (paying everyone), we created no hierarchy in pay. Everyone received the same day rate. The hierarchy was created via titles or screen time. For instance, maybe a job that would've been lower in the credits on a bigger set was considered a department head on this one. We made it clear to everyone, our usual collaborators included, that they could say no to the project. We couldn't go higher but would understand if anyone needed to pass. Everyone we offered a cast or crew role to, though, agreed to come aboard. Everyone did so enthusiastically. They cared about our story and our mission and the opportunity to play a role in that. Our crew was made up of mostly our core team of people who we'd worked with many times before. They knew we take care of people on set (feed them super well, don't overwork them (not since the crazy Summit learning experience) always reimburse costs, recommend them for paying gigs regularly) and that we make sure the work gets finished & seen and their contributions recognized. Many said they would've worked for free. And honestly, it was almost like they did. But we offered what we could to show we respect their time and talent, and I think that was appreciated — even if this project didn't pay their rent alone. (Part of our reason for only shooting on weekends was to make this project doable with other gigs and/or a day job.)

The same way the WHY of your film (why it matters and why people should want to be part of it) can get you free locations, donated food, and loans of props, the WHY can also be what makes other filmmakers/creatives join your project regardless of the pay. Don’t get me wrong; filmmaking is work. It is physical labor. It is mentally taxing. It requires unique skills and talent that need time (and money) to acquire. I believe in (and hope to one day be able to) paying people what they’re worth. But when only the people who have access to capital in a biased and inequitable system are the ones making content, then we end up where we’re only now starting to break out of in Hollywood — where everything that gets made is from one perspective and only represents one kind of experience. I grew up with a single mom who often had two part-time jobs on top of her full-time job, with zero access to the film industry. I’ve only been able to make content by approaching my career in this way. I’m so appreciative of the people who have chosen and continue to choose to offer their time and talent towards my projects because of the non-monetary benefits I try to make possible.

Shooting by Location & Rotating Personnel.

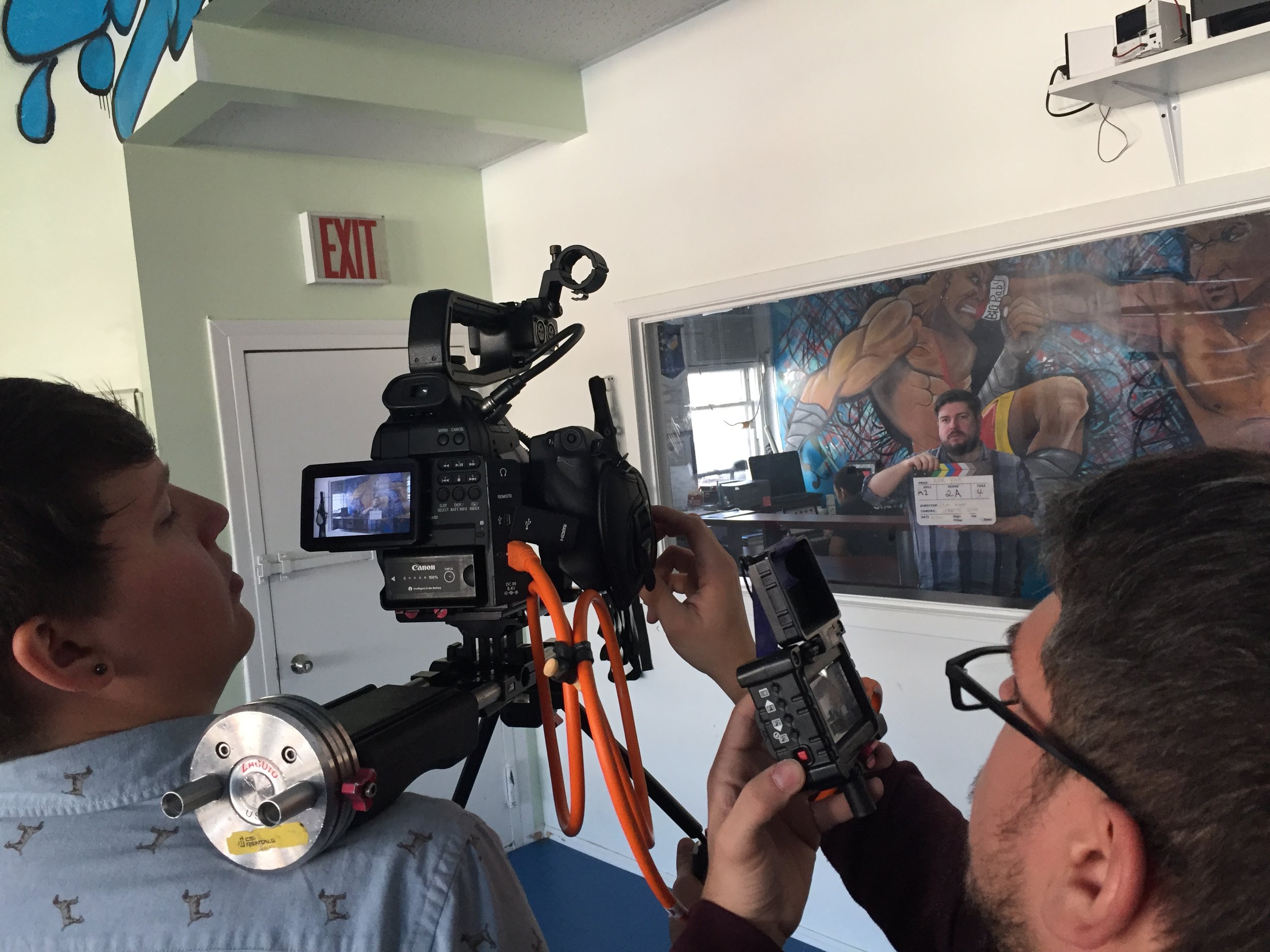

The day with our most crew on set.

You should always shoot by location, that’s filmmaking 101 (unless you have a good reason not to follow that rule, which is also filmmaking 101). However, locations really guided our shoot with this film. It’s an ensemble piece with a lot of locations, but many recurring. I’d say, it feels a lot like a TV series in that way. We tried to balance the production value of having multiple sets with being economical of our time. We found a way to shoot a 105-page script in twelve 10-hour days (many wrapped at 8, only one hit 12) largely by finding creative ways to shoot by location while limiting the amount of days each actor (in a core ensemble of 9) had to be on set. I wanted the actors to always have each other to react to, but there were a couple times where we shot one side of a scene on one day when we had one actor at a location and then the other side of the scene when we had the other actor(s) at that location. We never did this with scenes with only two actors, but definitely did it with some of our more light-hearted, donkey-centric scenes. We also had a rotating crew. Kelsey, our DP, our sound person, our makeup artist, and I were the only staples on set every single day. A couple days we rolled without an AD. We almost always had at least one AC each day, but that was split between 3 or 4 different people across the shoot. At our most hearty crew day, we had 11 of us behind the scenes; but most capped at 7. Having a skeleton crew meant we moved slower, but we compensated for that with decisions made in pre-production.

Shooting for the Edit.

This one is a no-brainer and should be done with any budget. However, it was extra imperative for this project. We knew we’d have limited time on set and fewer hands. We wouldn’t have the body count for running cables, moving lights, and swapping lenses swiftly. So we set out to make aesthetic choices that would minimize the need for all that. The film was shot with a natural look balanced by a touch of warmth. The lives of the characters at the start of the film are a little mundane. This paired well with shooting with mostly natural light. These people leave their curtains open and just kind of be. So, a lot of the time, we set up more flags and bounces than actual lights (of which we only had two most days anyway). It’s a dramedy, so high-key lighting was usually the way to go. And I prefer letting the actors find the blocking, so the more natural the set could feel and the less constrained they and the camera were by light placement and needing to avoid casting shadows, the better off we were. Peter Westervelt (our DP) did try to add texture with things like shades and interesting practical sources, but the goal was often for depth with consistency - not drama or overt contrast. Both Peter and I had seen the film Loving right around the time we started shot-listing and we both loved the look. We felt like the style really suited our film, where everything was shot in medium shots with medium lenses. Natural daylight played a big role. All the framing gave you a sense of the space that surrounds the characters. The drama was driven by the performances, not by the lens choices. So we decided to go in that direction. We chose one lens and essentially shot most of the film in mediums. Our objective was to make the framing reflect the relationships (who shares frames/who’s isolated, who feels tied to their surroundings/who feels free and loose), while still getting enough coverage to make performance and pacing decisions in post. We shot on a (Cooke Panchro) 40mm lens and never really had to swap it out. Only a couple days did we require a wider lens, and I believe only one day did we decide to go a bit tighter as an aesthetic choice for a scene. Most days, though, we didn’t even rent another lens and committed to our plan. Now, this definitely came with some limitations in terms of getting more varied angles and levels of closeness to be able to keep the cutting from feeling repetitive. It felt warranted considering the fact that the characters in this film are all kind of stuck in a way; so static, medium shots suited the feel of the film. But it was undeniably limiting and wouldn't work for all film styles and paces. (If you have more tech questions, hit up Peter. But if you’re curious, we shot on the Arri Amira at a discounted rental rate, initially courtesy of a filmmaker friend of a friend who owned the camera and then eventually via the cool people at Abel Cine after that dude bailed on us.)

Directing is in the Casting.

I had a directing professor in college who said that she was the kind of director who believed that 80% of directing is casting. I’ve met directors who don’t believe that, but I stand by it. I follow my gut and a big part of directing for me is in the audition room when I see what an actor brings. Maybe my professor and I are just those kinds of directors, and there are other kinds of directors that find success differently. But I can say, from running IndieWorks (watching hundreds of submissions) and attending countless film festivals per year, sometimes I find myself in conversation with directors that are super micro-managey and talk about pulling performances out of their actors, and then I watch their film and I’m like, “that’s what they pulled out?” Any actor that’s worked with me will likely tell you I’m a pretty hands off director on set. I’m decisive. I’m opinionated. I’m collaborative. But my notes are minimal. My takes are minimal. Maybe it seems like I’m holding back (sometimes that’s a strategy), but often I’m not giving a lot because I’m getting what I want. If I cast you, I have faith in you and I already believe you as the person you’re portraying. (This is why I have no interest in directing for hire unless I’m on board early and have final say in casting.) I’m a big believer in trusting the actors. I won’t take credit for someone’s talent. I will take credit for recognizing that talent and creating conditions to allow that portrayal to come out authentically.

I’m maybe going off on a long tangent here, but this is my last element, and maybe my most important of this post. Without the performances, About a Donkey wouldn’t be anything special. It’s a character-driven, dialogue-driven, ensemble piece about growth and relationships. We had quite an endeavor on our hands in terms of casting because we needed to find non-union actors who had the skills & suited the roles individually but also looked and had chemistry like a real family. For this reason, we started casting nearly a year before production and devoted a lot of time to meetups and getting the cast to bond before we began rolling. Now, while my focus was on the performances most of all on set, my time simply could not be. The way I worked with this fact, and how I work in general, is in the prep. I’m not gonna take an actor’s job and break down all of a character’s motivations and intentions for them. What I am going to do is talk to them about who a character is. I love backstory. I love psychology. I love exploring how this person got to where they are at the start of the film and what they want in the big picture. But the moments onscreen — the ways they bring out this person — those are the actor’s. I’m not trying to imply I don’t do any directing. I’ve been on sets where directors give the actors no feedback and also did no prep with them beforehand, and you can see that lack of direction in the acting too. With me, it’s about the conversation before getting on set, where it’s “this is what this means” or “this could mean this, what are your ideas?” I never tell an actor how to do a scene. I like to see what they just do. What is their gut go-to? What is their choice? Is it what I wanted? Did they surprise me and give me something I didn’t know I wanted? I feel, if I got to cast they way (who) I wanted and we talked about who this person is and why they are the way they are, 99% of the time they give me what I wanted in that initial choice on set because we’re on the same page. And then from there, it’s just “quicker” or “softer” or “hold that longer” — brief adjustments to make sure it’s translating. I know some actors like to explore on set — try something a few different ways per take. That’s just not an option with the kinds of productions this post is about. So, that exploring needs to be done on their own before the shoot. I trust my actors to make a choice, but I expect them to make a choice. We can dissect a scene off set, if that’s the way they like to work; but when they show up on set, I want them to know their character and how their character feels about something - which their reaction (choice) would inherently reflect.

With this film specifically, an ensemble talkie where the average scene has three characters (many included five or six, plus sometimes a donkey!), I had both a challenge and a gift on my hands. A challenge in that I needed to pay attention to so many performances all at once and try to know/meet the individual needs of each actor; but a gift in knowing that as long as I had my edit in mind, a perfect take would not be the priority. The priority was on getting the scene as a whole for the desired cut, and making sure the dynamics between characters felt authentic and the deliveries felt natural, even if a moment was off here or there in any given take. Maybe a character said the line right but it wasn’t quite there in their eyes — but I already know that I loved the other actor’s reaction to the moment in the reverse shot and that’s what I’d cut to there anyway, so I can confidently feel that I got it. It’s about that super sharp focus and anticipating the edit. In a punchy ensemble piece, staying on one character for multiple lines in a row is just not a thing. In comedy, it’s largely about the reactions. And so, on set, my mission was to follow the performances in a way where I could know I got it, even if not all in one take. Now, if the actors requested one more take, I always gave it to them. But sometimes, they’d ask if that last one was okay even though they felt like "maybe that one part wasn’t great," and I’d say “yes,” and I’d mean it because I knew that bit was great in a previous take. It’s that kind of attention (and memory or note taking) that a production schedule like this requires. This is something I’ve gotten good at with experience. Most of my work is ensemble-driven. The more I work this way, the better I get at identifying what I can and cannot cut around, and what I can create with the right coverage.

Now, I’m not perfect. There are times where I don’t give each actor what they need in every moment. It’s a process. I’m always learning — getting better at communicating and finding the right balance for each particular project. But it constantly goes back to the casting, and that was definitely the case with About a Donkey, where even if there wasn't the time to be super attentive with each actor on every day, they were talented actors who were the right fits for their roles and were on top of their stuff and knew who their characters were. So I had confidence every day that we got something great with every scene.